Lessons learned from across the pond

“Fishing is a way of life driven by passion,” said Colin Warwick as he kicked off the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council’s (MAFMC) Offshore Wind Best Management Practices Workshop this past February in Baltimore, MD.

Warwick, a third generation fisherman from the United Kingdom, now serves as the National Fisheries Liaison Officer for The Crowne Estate where he represents fishing interests to the offshore wind industry. Colin and two other commercial fishermen were invited by MAFMC and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) to share their experiences in negotiating ocean space between traditional fishing grounds and 22 operational offshore wind projects, totaling more than 1,000 turbines. Their story offers many lessons for the Mid-Atlantic, where commercial fishing is one of the longest-standing ocean industries and a single commercial wind turbine has yet to be built.

The biggest take-home message from the UK’s experience with offshore wind planning is that projects should not be sited and permitted without strong engagement from the commercial fishing sector from the beginning. Fishermen equate offshore wind turbines with a potential loss of fishing grounds, and therefore, a threat to their livelihoods. As fishermen attending the workshop pointed out, without a strong presence at the table by both wind developers and fishermen, the possibility of critical habitat loss and diminished productivity of fishing grounds increases: While offshore wind projects can offer a service to a region, the projects themselves can disturb the ocean floor with scouring, sedimentation, and channelization. To prevent this outcome in the next wave of proposed projects in UK waters, fishermen strongly recommend that the wind developer hire a fisheries liaison and a fisheries representative to develop and implement a local Fisheries Community Outreach and Communication Program for engaging and informing fishing communities throughout the offshore wind site assessment, construction, operations, and decommissioning phases. This approach has been effective in the UK and in opening lines of communication, creating transparency, and building trust between fishermen and the wind industry.

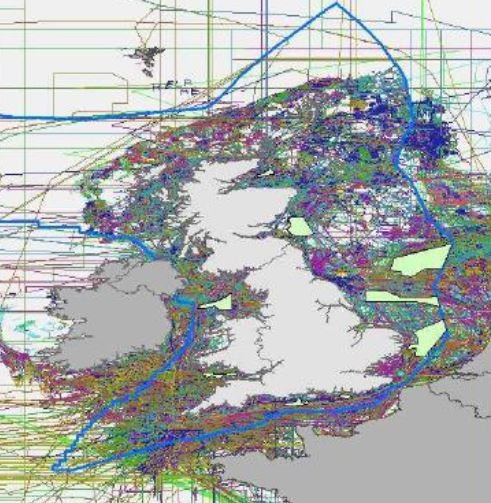

Another best practice highlighted by UK fishermen is the Crown Estate’s work in creating a spatial “fishing footprint” of the most productive and valuable offshore fishing grounds. Producing this footprint included requesting confidential chart plotter data from individual skippers in the UK commercial fishing fleet – data which record highly detailed information on their vessel’s movement, location, and fishing activities. Such data represent a fisherman’s trade secrets and are tightly guarded. However, with impending offshore wind projects possibly disrupting their livelihoods, fishermen were motivated to share their data with the Crown Estate in order to ensure that future wind projects avoid valuable fishing grounds. Fishermen were emphatic that plotter data must be paired with traditional knowledge of historic fishing grounds, which can only be found in the heads of the fishermen themselves. The stories Colin told underscored the vital importance of having commercial fishing liaisons and representatives at the table early and often when large-scale ocean decisions are made that could have significant impacts on the fishing community.

Through the Mid-Atlantic Ocean Portal project, the Portal team is taking the lessons from the UK to heart and working directly with Mid-Atlantic fishermen in a data development process called Communities at Sea. Through this project we are engaging directly with fishing communities to gather and incorporate advice on data summary methods, interpretation and map production. Like the fishermen in the UK, Mid-Atlantic fishermen are highly motivated to help develop spatial data that can support their interests in ocean planning processes. The Communities at Sea mapping project is a preliminary step in developing map layers that show some of the important ocean places that fishing communities have depended on for generations.

Share this story