The ‘Keystone Species’

Menhaden, aka bunker, mossbunker or pogy, are a small forage fish that are often used as bait by Mid-Atlantic anglers. The fish filter feed on plankton and swim in large schools that lure predators like bluefish, striped bass and humpbacks.

Gotham Whale attributes the return of the whales to a spike in menhaden in the New York Harbor area over the past few years. The organization conducts educational outreach on the importance of the species and advocacy work to help ensure its numbers remain strong.

“I call menhaden the keystone species in this area,” Granton said. “It’s bird food. It’s fish food. It’s shark food. It’s whale food. If you liken them to a house of cards, you pull out the menhaden and you potentially look at a biodiversity collapse.”

Again, what changed? Why the sudden surge in menhaden? Gotham Whale points to a handful of possible factors. Among them are catch limits that allowed stocks to rebound and an overall improvement in the New York Harbor area’s water quality, driven by cleaner water entering from the Hudson River and other tributaries.

“What we’re seeing now is 40 years’ fruit of the Clean Air and Clean Water Act and the fact that we still have the Marine Mammal Protection Act being enforced,” Granton said.

Gotham Whale founder Paul Sieswerda has another theory that points to Aug. 27, 2011. Hurricane Irene has been overshadowed by 2012’s Superstorm Sandy in the collective conscious of New York and New Jersey coastal residents. While Irene didn’t carry Sandy’s legendary wind force and tidal surges, those living inland will remember it as a catastrophic rain event that overwhelmed watersheds like the Passaic and Raritan in New Jersey and the Hudson in New York.

At the time, Sieswerda’s fledgling organization was giving what were billed as “whale-dolphin-bird watching adventures, because it was an adventure if we’d see anything.” He recalled the scene during a cruise he led a few days after Irene.

“We were hoping to see whales and the water was brown for miles and miles,” Sieswerda said. “We could not drive the boat far enough to get out of the plume. It was 20 miles down the New Jersey shoreline.”

But given time, Sieswerda believes, the silts and nutrients provided a jolt for plankton in the region’s waters. The menhaden followed, he believes, and so did their predators. In this scenario, a storm that devastated the human environment may have helped bring back marine mammals not seen in such high numbers in the area since whaling age.

“My big question is, how did the whales know and communicate [to others at sea], ‘Hey there’s a lot of good food around here,’” Sieswerda said.

Citizen Science

The songs of humpbacks have been a source of fascination for scientific researchers for over 50 years. However, little or no attention has been paid to menhaden’s sounds, and John Huntington is trying to change that.

Huntington, a sound professional in the theater world by trade, is working with Gotham Whale to apply his expertise to a scientific question: Do menhaden make unique noises that humpbacks can hear? On the trip, Huntington lowers a buoy with microphone equipment dangling from it into the water. His goal is to capture a recording of the inside of a menhaden “bait ball” – a tight, swirling formation they use as a defense against predators.

Although Huntington hasn’t yet succeeded in landing a mic in the center of a bait ball, he believes he may have picked up a distinct sound from those nearby. “It sounds like a woodpecker underwater,” he said.

Huntington is one of many individuals volunteering their time to help Gotham Whale fully explore the humpback population in the area’s waters. When there is a sighting, they document anything in the area that could influence their presence. Gotham Whale even offers a free beer from a list of partner establishments to members of the public who fill out a standardized form with information about their sightings.

“It’s citizen science, dare I say, at its best,” Granton said. ”We’re being very methodical about it. We’re taking photos of both dorsals and flukes [tails], we’re recording water temperatures, longitude and latitude, boats in the area, any other species in the area and how many.”

Gotham Whale has been compiling its marine mammal sighting data in formats that can be used to create maps. The organization is working with the New York Department of State to incorporate the data into the New York Geographic Information Gateway in a format that can also be used to bolster the Portal’s existing marine mammal map collection, especially in the nearshore area off New York City, Long Island and New Jersey.

Using Data to Identify High-Risk Areas

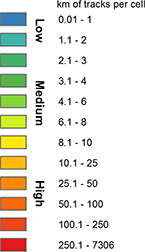

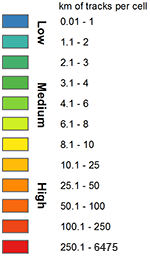

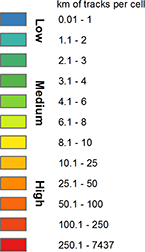

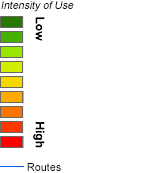

Brown has been conducting a comparison of Gotham Whale’s humpback locations with the Portal’s shipping data to identify areas where the risk of ship strikes is greatest. The map above contains U.S. Coast Guard Automatic Identifying System (AIS) data showing annual concentrations of cargo, tanker, tug/tow and passenger vessels in the vicinity.

Brown has published her work and is helping to build awareness among those traveling what are some of the busiest marine highways in the world (click here to view her presentation at the 2019 Mid-Atlantic Ocean Forum). This includes recreational boaters, who she said sometimes travel the area at high speeds and get too close to the whales.

“Here it’s so new that people don’t know how to react,” she said.

The map now shows recreational boating traffic data compiled through surveys by MARCO and the Monmouth University Urban Coast Institute (for the Mid-Atlantic) and the Northeast Regional Ocean Council and SeaPlan (for New York and New England).

Brown, a former staff member at the Marine Mammal Stranding Center in Brigantine, New Jersey, said they have seen whales in the area with injuries consistent with vessel strike. Hitting a massive humpback – especially with a small boat or recreational craft like jet skis – also poses a risk to boaters, she said.

“[The humpbacks] are playing in traffic, which is unfortunate,” Sieswerda said.

Sieswerda said he looks forward to the expansion of non-marine mammal data on the Portal, such as an upcoming collection of commercial fishing maps that will show where activity was highest during several past windows of time. Such data could offer insights on how populations of key prey species are shifting, he said.

“[The Portal] makes you able to see those big pictures in ways that might not have been possible before, and it’s only going to get better and better and bigger and bigger,” Sieswerda said. “I think it’s a wonderful process and we feel good that we might be able to contribute.”

Story by: Karl Vilacoba, Monmouth University Urban Coast Institute. He can be reached at kvilacob@monmouth.edu.